by Ingrid Lehmann, 20 January 2020

1. A peace process with many hurdles

I was 30 years old, working as a junior officer in the Executive Office of the Secretary-General of the United Nations in New York. In August 1978, I was happy to take time off and joined a journalist friend in the beautiful archipelago near Stockholm, Sweden.

The vacation ended unexpectedly when the Chief of Cabinet of the Secretary-General called me and asked that I return to New York as soon as possible to join the first UN survey mission leaving for Southwest Africa, a territory then still illegally administered by South Africa. I was intrigued as I had followed the negotiations since the mid-1970s, and broke off my holiday to fly to New York, get very brief instructions from my boss and get on another plane with colleagues leaving for Namibia the next day. The plane was a C-130 cargo plane, lent to us by the United States, which was a strong supporter of the UN’s efforts in Southern Africa under President Carter. The then US-Ambassador to the UN, Don McHenry, personally saw us off.

At that time, I was still able to sleep in cargo planes without problems and woke up on arrival to find out that I really had no function in this survey mission except to assuage the German Foreign Office. They had wanted to send one of their own diplomats, a request that was refused by the head of the UN mission, Martti Ahtisaari. Sitting by the pool in the Safari motel in Windhoek doing nothing was not my thing; when the mission split up into various civilian and military components, the only people who agreed to have me along were the small group of UN military officers. The civilians apparently considered me a spy from the Secretary-General’s office and saw no useful function for me, while the UN force commander designate considered me an ally with political know-how.

Travelling with the military turned out to be an advantage, as the South Africans, in 1978, had decided to go along with the UN’s plan for the independence of Namibia and treated us as honored guests. I thus saw much of the country (which is half as large as Western Europe), hopping on military planes and helicopters and sleeping in tents. I fell in love with the vast beautiful country and met some impressive locals, with whom I would stay friends for years to come. We returned to New York full of optimism that the Western settlement plan would work out and would be implemented shortly, but then South Africa reneged on the agreement and the peace plan “435” (named after the Security Council resolution) went on hold for another 11 years.

During the next decade, I thought about Namibia often, followed the negotiations from afar, went on another peacekeeping mission (Cyprus) and joined two other UN Departments as Political and Information Officer. In 1988, there was a thawing of positions between SWAPO (South-West African People’s Organization), and the South Africans, as numerous cold war conflicts came to a close. Agreements were signed and our old plans for the independence process were pulled out of drawers as implementation this time seemed to be for real.

In 1989 I was fortunate to be seconded to the new UN survey mission to prepare for the independence process which was to start on 1 April. We were back at the same pool in the Safari Motel outside Windhoek when SWAPO’s military wing, in violation of the cease-fire agreement, led an incursion in the North of the country. We feared the worst, as South Africa threatened to throw us out of the country. I started calculating how long it would take to drive to Botswana to escape the threatening war, and began to hoard fuel in jerry cans. But crisis talks conducted by UN diplomats in Angola were successful, and the mission could finally begin its work in earnest.

I became head of a small district office of the UN Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) and stayed there throughout the registration of voters and the campaigning of parties, watching over a political “code of conduct”. Prior to the elections in November 1989 I became head of the whole Windhoek electoral district which ranged from east of the capital to Solitaire in the west, nearly 350 km away on unpaved roads. It was a good year of very hard work, some political turmoil, as well as physical attacks on members of the UN mission, but our work was crowned when the first free and fair elections took place in Namibia under UN surveillance. A strong Constitution was worked out with the help of UN and other international legal experts, and the country celebrated its independence in April 1990.

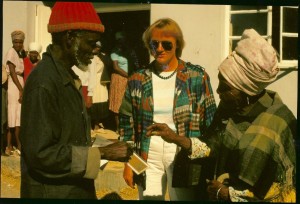

Voter registration, 1989

Lesson 1: An international peace process following protracted civil war is rarely a smooth linear affair, but often entails setbacks and may take decades to come to fruition. Patience and a strong will by the international community including the superpowers are required to see fruition. The Namibian civil war, in other words, in 1989/90, was “ripe” for settlement.

2. Namibia – independent and democratic

The country had a good start, plenty of good will internationally, material support and training assistance. Its leaders had been well educated during their time in exile abroad, and had matured through the long liberation struggle. Western Europe, predominantly Germany as a former colonial power with many residents with German passports, maintained a keen interest for years to come and provided generous aid. The memory of the brief but brutal German colonial dominance in South-West Africa (1884-1915) stays vivid among the Herero and Nama people in Namibia until today, but resentment against the whites never flared up as it did in Zimbabwe or South Africa itself.

When my husband and I visited Namibia in April 2005 we were both impressed by how well the country was doing and the feeling of good will which persisted among all major ethnic groups. Blacks had advanced politically and economically with independence, and primary and secondary education were generally available. Opportunities were created for hard-working talents to advance to management positions. Training institutes prepared young people to become involved in the booming tourism industry. English was the official language, even though the 10+ ethnic languages were cherished and considered part of the country’s cultural heritage. Racism was not eliminated, but racial equality was enshrined in the constitution. There was a growing middle class among mixed-race and black groups, even though large percentages of blacks still lived in poverty. The former townships, a result of forcible relocation by the South Africans under Apartheid, had some paved roads, and cardboard shacks were increasingly replaced by concrete houses.

Of great significance was the development in South Africa itself. Nelson Mandela was freed in early 1990 and negotiations (also with several setbacks) resulted in the end of Apartheid in South Africa, and the conduct of free and fair elections in 1994 led to a black majority government. Many whites threatened to leave the country, but the reconciliation process was, under Mandela, a tool of healing. As far as Namibia was concerned, Walvis Bay, the second largest port in Southern Africa, was finally, after protracted negotiations, returned to the country by South Africa. Namibia’s regional neighborhood thus became increasingly peaceful, with Botswana, a stable democracy in the East, and Angola and Zambia in the North.

During our visit in 2005 we noticed the friendliness and kindness of locals, in the North of the country as well as in the coastal towns. There was, compared to South Africa, a relatively low crime rate, but it was noticeable that the approximately 5 percent whites (both German Namibians and Afrikaaners, i.e. descendents of Boers) held about two thirds of the farmlands. This fact continues to be a source of friction with largely landless black poor.

We were again struck by the beauty and variety of scenery in the thinly settled country. And we visited our German-Namibian friends now living in Swakopmund who complained about the government and the privileges the black elite accorded itself, but led pretty comfortable lives in the German cultural center. German was still widely spoken in Swakopmund and those traditions were preserved.

Lesson 2: Continuous long-term democratic governance is a benefit for the economic and social development in a country. Changes in landownership are slow and continue to be a source of dissatisfaction for the largely black landless population. Multi-racial society is slow in establishing itself after decades of suffering under the system of Apartheid.

3. The observers return – 2019-2020

Last year, my husband and I decided to revisit Namibia. We spent four weeks this December/ January in the country, following our own favorite paths by avoiding the major tourist sites, such as the Etosha pan and the famous Sossusvlei dunes, “counter-programming” as much as possible.

In our first stop, the capital Windhoek, we immediately discovered how much building had taken place: boutique hotels, where none were before, large, clean shopping centers with restaurants and open spaces to sit and eat. It made our own shopping mall in Salzburg look crowded and pushy. The population of Windhoek had grown significantly, and a few sites of the German colonial days had disappeared, but some of our favorite places, such as the Craft Café in the Namibian Arts and Crafts Center, were still functioning and serving healthy food. Tourists were much less visible here: it was a week before Christmas.

In Swakopmund we found a different situation: groups of tourists, both from within the country and from abroad milled around everywhere, restaurants nearly all required reservations and one had to be early to book popular tours, such as a new “fat-bike tour” through the center of town, the black township Mondesa and the dunes. Our personal guide, a young German Namibian university graduate called Chris, took us on one of the most memorable bike tours of my life.

There seemed to be a recent influx of young whites into Swakopmund, as it clearly is the most popular town with a high quality of life and a multitude of outdoor activities, such as ocean swimming, kayaking, surfing, dune riding and biking. The heat of the inland was not felt here, as cool breezes from the South Atlantic combined with morning fog to make the weather very comfortable.

However, the tour through Mondesa showed us that the majority of the black population still lives in abject poverty: There were few paved roads, problems with garbage removal and heating with scarce wood, which made the air difficult to breathe. The unemployment rate overall is 33 % in the country, but in the townships it is much higher. As in many African countries, HIV continues to be a problem in Namibia: the infection rate is high with 12 percent. While literacy is high with over 90 percent, only 20 % of Namibians had access to the internet in 2016.

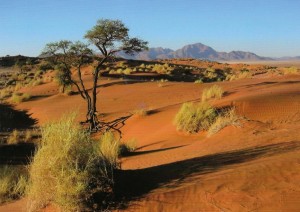

While the overall population of Namibia has increased from 1,4 million in 1991 to 2,3 million in 2016, its population density is still one of the lowest in the world: 2.8 people per square km. The large open spaces and beautiful deserts in the National Parks of the Namib Rand and the Namib Naukluft attract predominantly individual travelers and smaller groups; rarely does one see the large tour buses that are a traversing Europe in ever-increasing numbers. While it was often quite hot in the middle of the day in December, when we measured at times 43 degrees celsius, hardy bicyclists on loaded touring bikes were occasionally seen struggling along on windy, dusty roads.

Tourism is one of the main sources of income now, but it has not (yet) led to the “overtourism” seen in other popular destinations in Europe and the Americas. There continues to be an ecological consciousness among hosts and their guests, with many farms and lodges taking only smaller groups and supplying themselves through their own wells and solar energy. A major problem from the point of view of locals and travelers is that access to some of the main tourist sites is still on gravel roads that, due to high traffic have turned into washboard-like surfaces. Traffic accidents continue to be one of the major causes of death in the country.

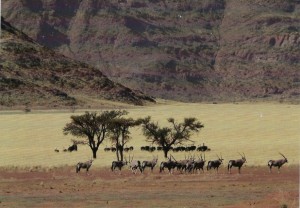

15 years ago we did something like this – for three days!

In addition to staying in two remote lodges over Christmas and New Years we revisited an environmental training Centre called NaDEET (Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust) which has, since its inception in the late 1980s, trained tens of thousands of Namibian secondary school children in conservation, sanitation and ecological issues. We were very impressed by how this training center has maintained itself in a remote location of the Namib desert, and how it has expanded its activities since we last visited 15 years ago. See www.nadeet.org.

NaDEET camp site

Lesson 3: Education and job training are a powerful force for social and economic advancement among people from poor backgrounds. The middle managers in two lodges and one hotel were self-made people with excellent English, whose work, morale and professional demeanor would be a credit to tourist service establishment anywhere in the world.

4. Notes on a scandal

As far as politics was concerned, every other person we talked to during our four weeks in the country expressed outrage at the latest (and most shocking) governmental corruption scandal, the so-called “fishrot- scandal” which involved selling Namibian fishing rights to an Icelandic- based multinational company called SAMHERJI, which is now the biggest recipient of fishing quotas off the Namib coast. Two ministers (including the Ministers of Fisheries and the Minister of Justice!) have reportedly been bribed; they and three of their associates were in jail awaiting trial in January. This scandal was uncovered initially by Wikileaks which received detailed information about the bribes from a whistle-blower, a former manager of SAMHERJI with first-hand knowledge. It was also picked up by the newspaper The Namibian and other local papers. The scandal was further analyzed in-depth by Al-Jazeera which produced a striking documentary “Anatomy of a Bribe” (https:Aljazeera.com.anatomy).

The people we spoke to in Namibia were outraged and complained that this wide-spread corrupt sell-out led to the bankruptcy of local companies and caused large-scale loss of jobs among Namibians. The Icelandic company was supposed to pay for infrastructure projects in Namibia which never materialized.

While this scandal received nearly no international attention other than in Iceland and on Al-Jazeera, Namibian newspapers covered it. People apparently demonstrated in front of the Namibian Anti-Corruption Agency which was founded in 2006, forcing the hands of the prosecutors and police. The scandal overshadowed the presidential elections in November 2019, where Swapo, for the first time, lost its absolute majority.

Lesson 4: It is not enough to have regular democratic elections in a country, when the large majority of the population does not have access to the internet or other unbiased information. It is important to strengthen the independent media and watch-dogs such an anti-corruption agency separate and independent from the ruling government. International NGOs such as “Transparency International” need to be engaged in Southern Africa.

5. Summary and outlook

My long engagement with Namibia has made it possible and instructive to look at the development of Namibia over four decades, which have spanned the gestation, birth and the coming of age of independence in Namibia . This retrospective combined with current political analysis showed me that

. 1) The engagement of Western countries in Southern Africa has significantly deteriorated since the 1970s/1980s. Economically speaking, China is more active in this region than Europe, building desalination plants which are critical to Namibia’s future development, equally much-needed water conduit pipelines, and a new uranium mine. Europe’s absorption with itself and the conflicts in Northern Africa and the Middle East has led it to ignore large parts of Africa which could have been used as examples for the sort of development wished for conflict areas, such as the Sahel.

. 2) When we look at the involvement of the United States in Southern Africa in the 1970s, under President Carter, the contrast to President Trump, who called African cities “shit-hole towns”, is striking. The United States has clearly shifted its attention to areas of the world where there is little tradition of peaceful resolution of conflicts, such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

. 3) The future of tourism in Namibia will be at a crossroads when larger groups seek access to remote national parks, surpassing the capacity of this fragile country to absorb these groups without major damage to its environment. Careful planning and continued training in ecology and conservation will be needed, particularly when faced with climate change (drought).

. We were largely positively impressed by Namibia today. The apparent state of governance, despite or perhaps because two former government ministers are at present behind bars accused of massive corruption, is impressive. There are states in Europe and in America which are not better governed. We venture to say that, if the rest of Africa were as well managed as Namibia, the entire world could breathe a sigh of relief.

. We can’t wait to go back!

.

.

Dear Ingrid,

Thanks for this encouraging article. I am glad to read that Namibia is doing well.

As you know, I was in UNTAG as well and, like all of us, I have fond memories of the country and the operation.

I am not sure what the reasons are for Namibias apparent success or at least its avoidance of descent. You name a few, and they are well taken, but the longer I observed conflict zones and the more operations I witnessed, the more I came to the conclusion that the human qualities of the leadership play an important if not decisive role.

I have always been hesitant to visit places that I remember positively, but your article makes me think of returning to Namibia one of these days.

Warm regards,

Wolfgang