by Ingrid A. Lehmann

(Editor’s Note: This article is a version of a chapter in the book, Communication and Peace: Managing an emerging field, Eds. Hoffmann and Hawkins, Routledge, London, 2015)

Introduction

When the United Nations launched its first peacekeeping operations in the 1950s, the concept of using third party military units to create conditions for peace was in its infancy. Inevitably, media reporting of those first peace operations was scanty. Public impressions of these efforts at conflict resolution were covered by relatively few print media and only some television news programs.

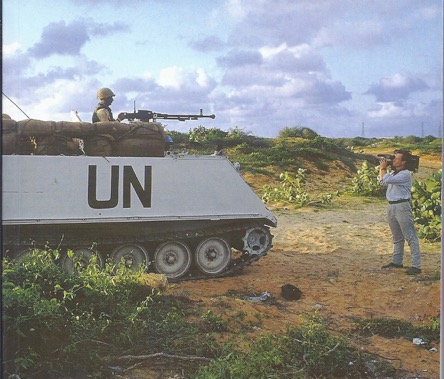

However, conflicts in the 1990s in the Balkans, in Somalia and in Rwanda occurred nearly simultaneously and attracted 24/7 instant news coverage around the world. UN peace operations which were enmeshed in these new wars were thus propelled into the limelight. The media was systematically used by parties to the conflict to propagate hatred and violence, putting international peacekeepers increasingly on the defensive. Consequently, UN operations deployed in these conflicts received much unfavorable publicity and were, in more ways than one, caught in the crossfire (Lehmann 1999, 2009; Alleyne 2003; Loewenberg 2006; Lindley 2007; Abusaad 2008; Egleder 2012).

Finally, the United Nations itself had to recognize the power of communication as a critical support for its peacekeeping operations. Beginning in 2000 a new peacekeeping doctrine evolved following the issue of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations – the so-called “Brahimi Report” – which also addressed the question of public information capacity. Simultaneously, substantial reforms of the UN’s own Information Department (DPI) were undertaken by senior management under Secretary-General Kofi Annan. These reforms resulted in a series of policy papers and guidance notes which established a strategic approach to managing information during peacekeeping and post-conflict peacebuilding. Throughout this process, which lasted several years, strategic communication was the declared goal of the UN in which the concept of peace communication was implicit rather than explicit.

In order to analyze the effectiveness of the new communication policy this chapter will look at three peacekeeping operations where the UN’s ability to build public support and respond to criticism was tested:

1. The UN operation in Kosovo: “Peace Journalism” at work?

2. The UN’s role in the cholera crisis in Haiti (2010–2013): failed scandal- management; and

3. Sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers in the Congo.

The comparative brevity of this article will not allow a comprehensive analysis of the public dimensions of those peacekeeping operations. By selecting critical incidents or crises for the missions concerned we will look at how these challenging situations were handled, and to what effect.