A review essay, based on Dag Hammarskjold: Markings of his Life, by Henrik Berggren

Reviewed for Peacehawks by Jamie Arbuckle

You asked for burdens to carry – And howled when they were placed on your shoulders.

Dag Hammarskjold, Markings

Introduction

On 4 November 1956 the General Assembly of the United Nations requested the Secretary General, who was then Dag Hammarskjold, “to submit a plan for … an emergency international United Nations force to secure and supervise the cessation of hostilities” in the Middle East. Peacekeeping had been born. It was five days before my sixteenth birthday, and I was already a voracious reader and a heavy consumer of news. I said to my father, “I have seen the future, and it has to work.” My father, who had lived through two World Wars, the Great Depression and the Korean Conflict, was in my memory of those distant days, reserved in his reaction. But this was to be my world, not his – his work was largely done. Here was the beginning of my adulthood and the grounding in me of my vocation: I was to be a soldier for peace.

So for me any talk or remembrance of Dag Hammarskjold is intensely personal, sending me back to my earliest beginnings, and spanning much of the rest of my professional life, and beyond. The real prime mover of the birth of peacekeeping was Lester B. Pearson, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts (so was Hammarskjold, posthumously), and was later Prime Minister of Canada as my adopted country became one of the leaders of international peacekeeping operations. Shortly after my retirement from the Canadian Army, I met my wife as we both worked at the Lester B. Pearson Canadian International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Nova Scotia. Today on our shelves we each have our heavily annotated copies of Markings, which we have each carried for over 50 years.

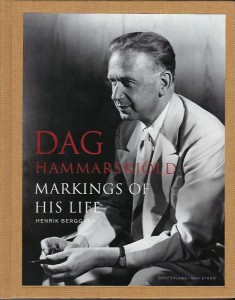

Henrik Berggren’s book Dag Hammarskjold – Markings of his Life is a skilful, entertaining and entirely useful re-telling of the more personal aspects of the life. It is especially important that it is retold afresh in and for this generation, from whom these important events might otherwise slip away. The book is generously illustrated, affording us a real feel for the personalities and the times.

This book might easily be dismissed as hagiography, but Hammarskjold’s was in many respects an exemplary life, and hagiography does not imply inaccuracy. In these days of baseness of aims and personalities, and the almost total absence of international statesmen of character, there is certainly much to be gained from a review of such a strongly moral character, who also got things done, who also delivered on promises. That the book is so strongly personal in its scope does suggest to me a mild corrective in relating in somewhat more detail what I regard as the most important events of Hammarskjold’s all-too-brief time, his eight-year ministry (1953-1961). These were, firstly, the events of 1956, when peacekeeping was born, and Hammarskjold defined himself and his job, “for succeeding generations”. Then we will have more to say on the subject of the birth of peace enforcement operations in the (former Belgian) Congo in 1961, and then their near-disappearance from the UN’s tool kit, for the next more-than 30 years.