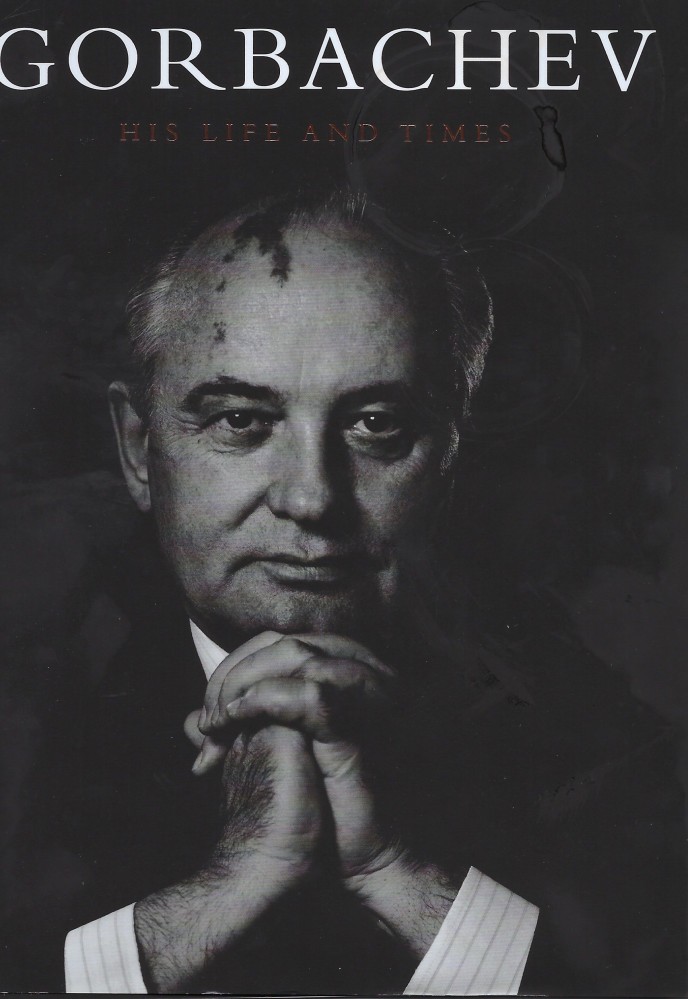

A review essay for Peacehawks, based on Gorbachev – His Life and Times, by William Taubman

by Jamie Arbuckle

We learn from history that we do not learn from history.

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831

INTRODUCTION

Mikhail S. Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 11 March 1985. He was 53 years of age. In the previous three years his three predecessors had died in office, aged 76, 80 and 79 (respectively). The 12-Member Politburo, when he first joined it in 1980, averaged over 70 years of age. The winds of change were blowing, and Gorbachev was to be of that wind.

With his inaugural acceptance speech he launched his nation on a dual program of “perestroika” (restructuring) and “glasnost” (openness). These two concepts, long debated and refined among his closest advisors, introduced profound changes in the governance of the Soviet Union. Among the entirely unintended consequences of this were that, within five years, communist governments throughout Eastern Europe were swept from power. The Paris Summit of the Conference on Cooperation and Security in Europe (19-21 November 1990) adopted the Charter of Paris for a New Europe and drew the Cold War, which had against all odds remained cold for forty-four years, to a peaceful close.[1] The Soviet Union imploded into 15 individual republics.

This story, which will be broadly familiar to most of you who lived it, is well and skillfully told in Taubman’s book. But we are learning that it is not enough that we tribal elders know the history of our times; it is worthwhile, indeed necessary, that such stories are retold in each generation, so that they not slip away from us under pressure of no less alarming and urgent events of these succeeding days.

I joined the army as the missile gap was being touted and dire warnings sounded; I became a non-commissioned officer in the year of the Berlin Wall; I was commissioned an officer in the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Like many of you, I lived those times, and I can never forget. But our succeeding generations must not be condemned to relive our times. The key for their future is knowledge: of what happened, the whys, what worked, what didn’t, what might have been avoidable, and what probably wasn’t. Theirs is an age of clear and present dangers, and knowledge is the only thing that might deliver the society of your children, and your grandchildren, from a repetition of our past mistakes and failures.

The Cold War lasted from 1946 to 1990, and dominated the world as did the two World Wars which preceded it. And what are our successors to make of all this? More importantly: what are the Trumps and the Putins, products of as well as successors to those times, making of them now? It seems to us that sabre-rattling has replaced diplomacy, and zero-sum games have replaced negotiations. So books like this are important, and this one is a particularly well written record of what we must not forget, for “those who do not study history are condemned to relive it.”

But I want in this review essay to get beyond an appraisal of this book, excellent as it is.

The striking thing about Gorbachev’s “challenge” (as Time called it in their issue of December 19, 1988) was not that it was not welcomed by the audience for which it was intended- that was natural and was foreseen, but rather how negatively it was greeted in the West, whose fondest hopes for a peaceful end to the Cold War were being realized. And it is this reception of glasnost in the US, in NATO and generally by western analysts, on which I want to focus this article.

Western defense strategy was based on two pillars: the missile gap, and the conventional force gap. Because of these mythical gaps, western defenses were to be for a half-century based on a threat of first use of nuclear weapons by NATO. This highly dangerous policy is still in place today, but the bases for it, the famous gaps, were never more than worst-case imaginings, and they are even less valid today.

We now need to mind those gaps.